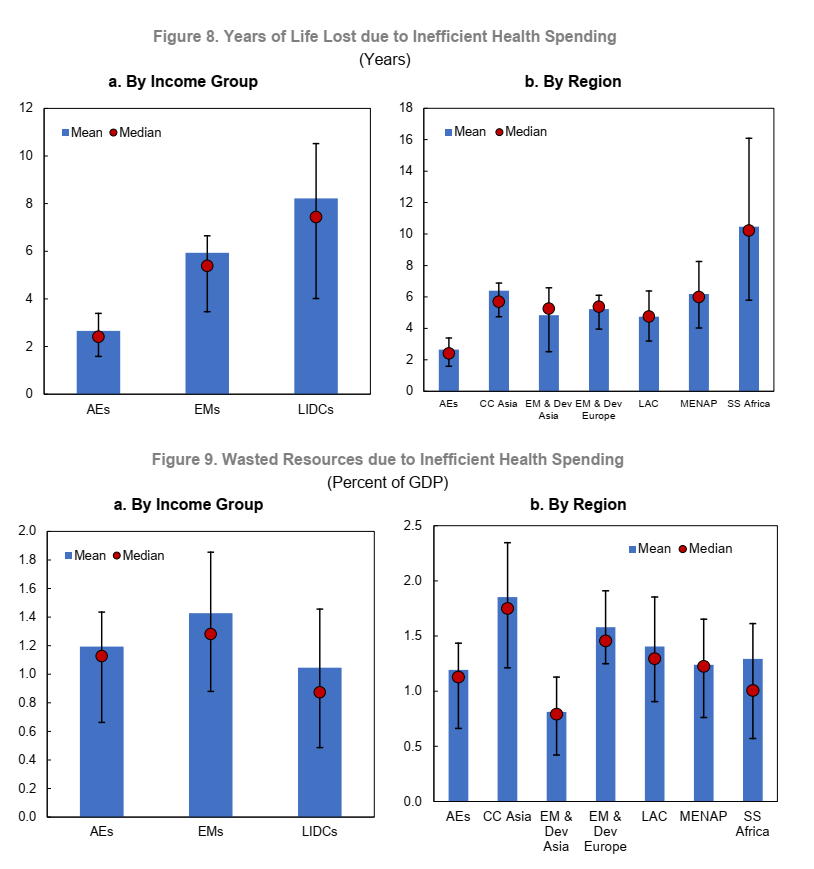

Health issues are high on public policy agenda. Health-related Sustainable Development Goals are yet to be achieved, COVID-19 pandemic is still on, and ageing population requires additional health services. Demands for health expenditures are at an all-time high all across the globe, while the fiscal space is limited. Not surprising, policymakers focus attention on ensuring that resources are used efficiently. This chart of the week shows losses—in terms of years of life and percent of GDP—due to health spending inefficiencies. It comes from the recent IMF Working Paper “Patterns and Drivers of Health Spending Efficiency”, which considers input- and output-oriented measures of (in)efficiency, depending on country distance from the frontier of expenditures-life expectancy.

The paper explores other patterns in efficiency across income groups, regions, and time, and the fiscal and years-of-life losses due to how health resources are spent. It goes further in exploring the question of drivers of health expenditure inefficiency, focusing on three major drivers: universal health coverage with essential services, income distribution, and corruption.

Universal health coverage is a crucial driver of health efficiency. If each country were to achieve, for each policy variable, the 75th percentile of its income group, low-income developing countries (LIDCs) would on average benefit from an increase of 3.4 years of life, while emerging markets (EMs) would gain 2.2 life years. Measured in expenditures savings, EMs and LIDCs to benefit from 0.39 and 0.37 percent of GDP. A more equitable distribution of income brings lower but still substantial gains in life expectancy by 1.7 and 2.1 years for EMs and LIDCs, respectively—or bring in savings of 0.17 and 0.12 percent of GDP. Better control of corruption is important, especially for EMs, which can benefit from an additional 1.6 years of life expectancy or avoid the waste of 0.27 percent of GDP in health spending. LIDCs gain 0.7 years of life expectancy or save 0.1 percent of GDP.