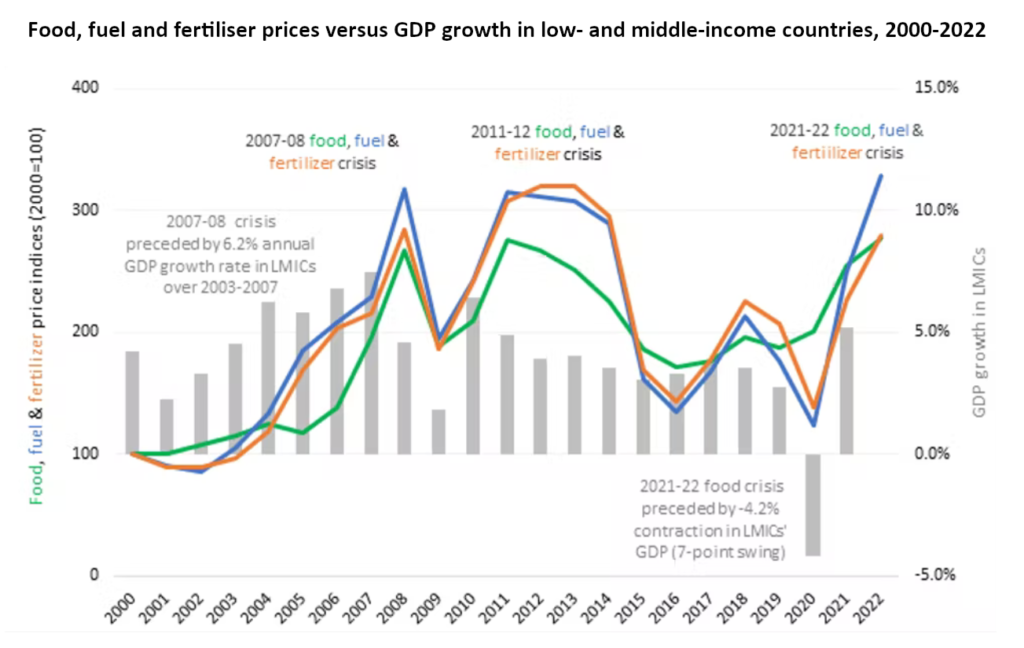

Informal employment attracts a lot of attention, because it is widespread but associated with risks. It lacks of insurance against shocks, and therefore directly related to vulnerability to poverty. Many Social-Economic Impact Assessments of COVID-19 showed that informal workers were particularly hit hard by turbulence in 2020-21. However, measurement of informality is not that simple. Most often used definition is lack of social and/or health insurance. Meanwhile, research has shown that formalization does not automatically lead to poverty reduction.

While there are many reasons why this link does not work automatically—flexibility of informal arrangements, hidden costs of formalization—one reason could be how we measure informality. We usually measure welfare on the family level, using household income or expenditure and assuming that families share these. However, informality is usually measured and analysed on individual level—individual workers, family firm, the household head—without making assumptions how risks and benefits of informality are shared in family. (There is a rich and growing body of literature on migration as a risk sharing, for instance “Risk Sharing and Internal Migration”) As a result, policies related to poverty reduction and reducing the risks of informality are often designed with different groups in mind—families and single individuals respectively.

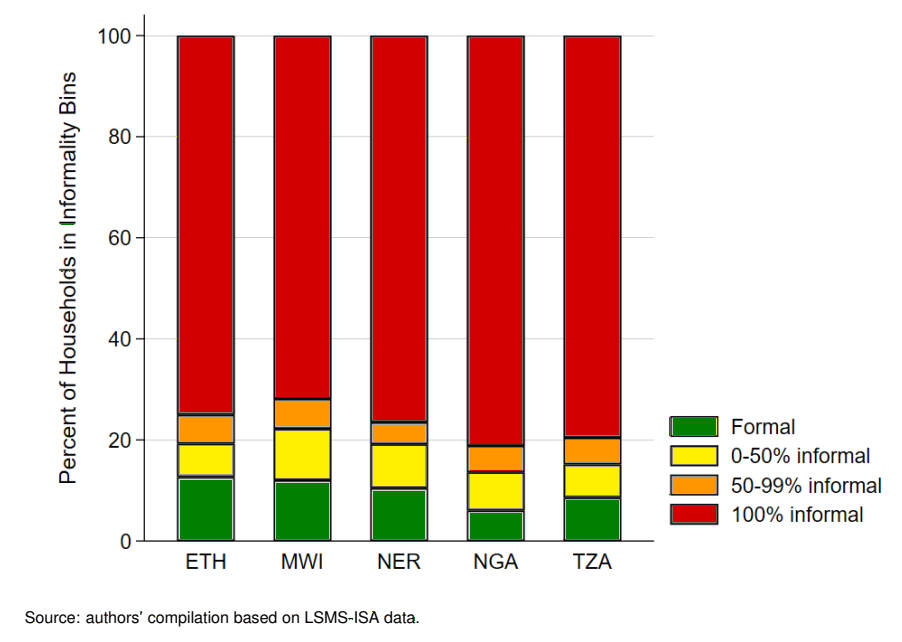

This chart of the week comes from a recent paper “Welfare and the depth of informality. Evidence from five African countries”. It shows that there are shades of “informality”, rather than simply “Yes” / “No” dichotomy. The paper further investigates the relationship between welfare and informality at the household level. The findings confirm the nonlinear relationship between welfare and informality—families with some formal incomes are as well off as families with only formal income. Moreover, paper suggests that moving to full formality only translates to meaningful welfare improvements if the household income gain is sufficiently large.