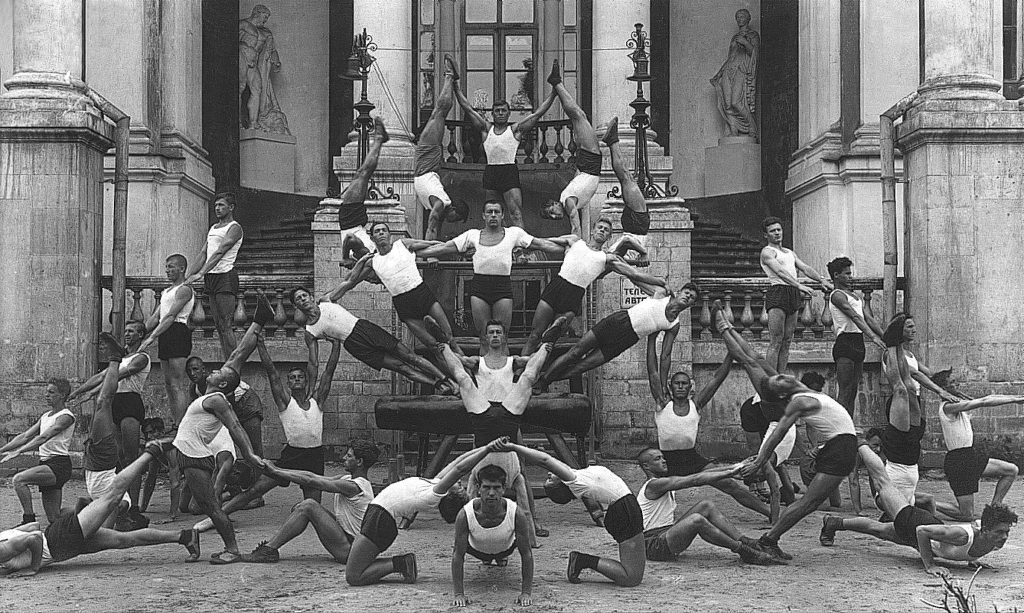

Every day you seamlessly interact with computers, whether it’s your laptop, phone, tablet, or ATM screen. But do you know that the pivotal moment responsible for this occurred back in the 1970s? This moment was a powerful question asked by Alan Kay: “How can we make computing more accessible and intuitive?”

In the 1970s, Xerox PARC was a hotbed of innovation, home to visionaries like Alan Kay and Douglas Engelbart. This question inspired the development of groundbreaking technologies such as the graphical user interface (GUI) and the mouse, culminating in the creation of the Xerox Alto. Despite Xerox’s failure to capitalize on these innovations commercially, the ideas born at Xerox PARC were picked up by Microsoft, Apple and others, shaping the digital landscape for decades.

The powerful question sparked a paradigm shift in computing.

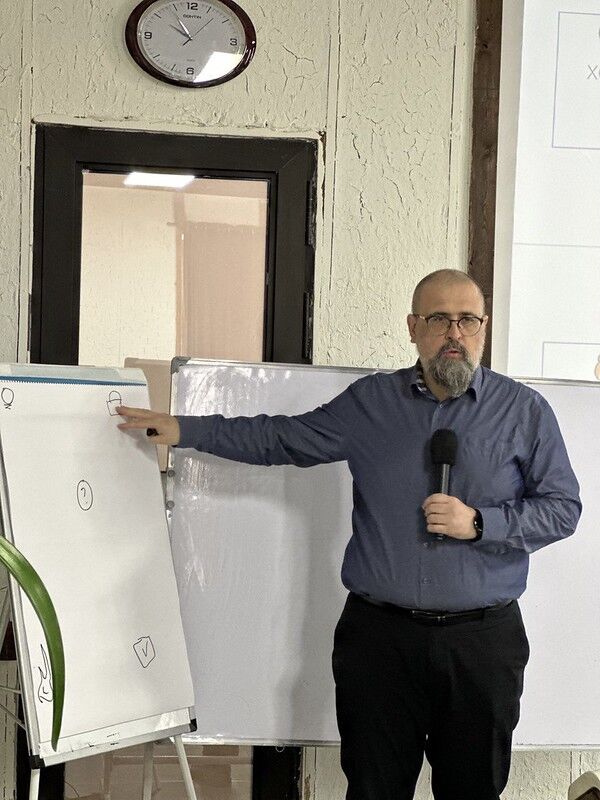

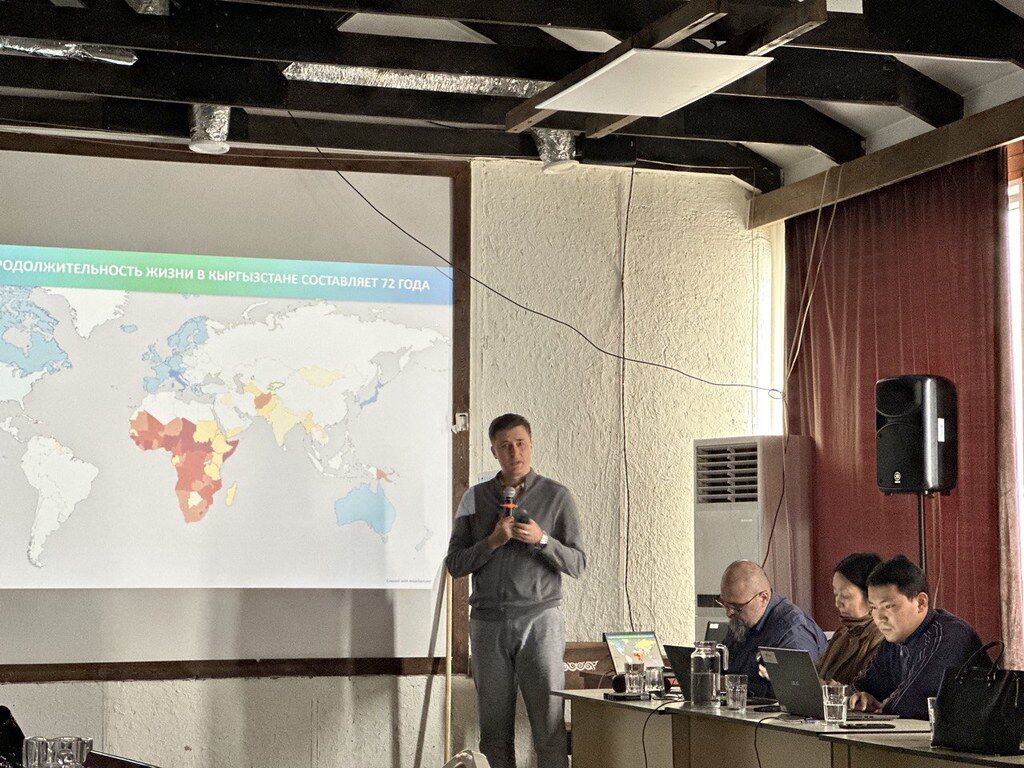

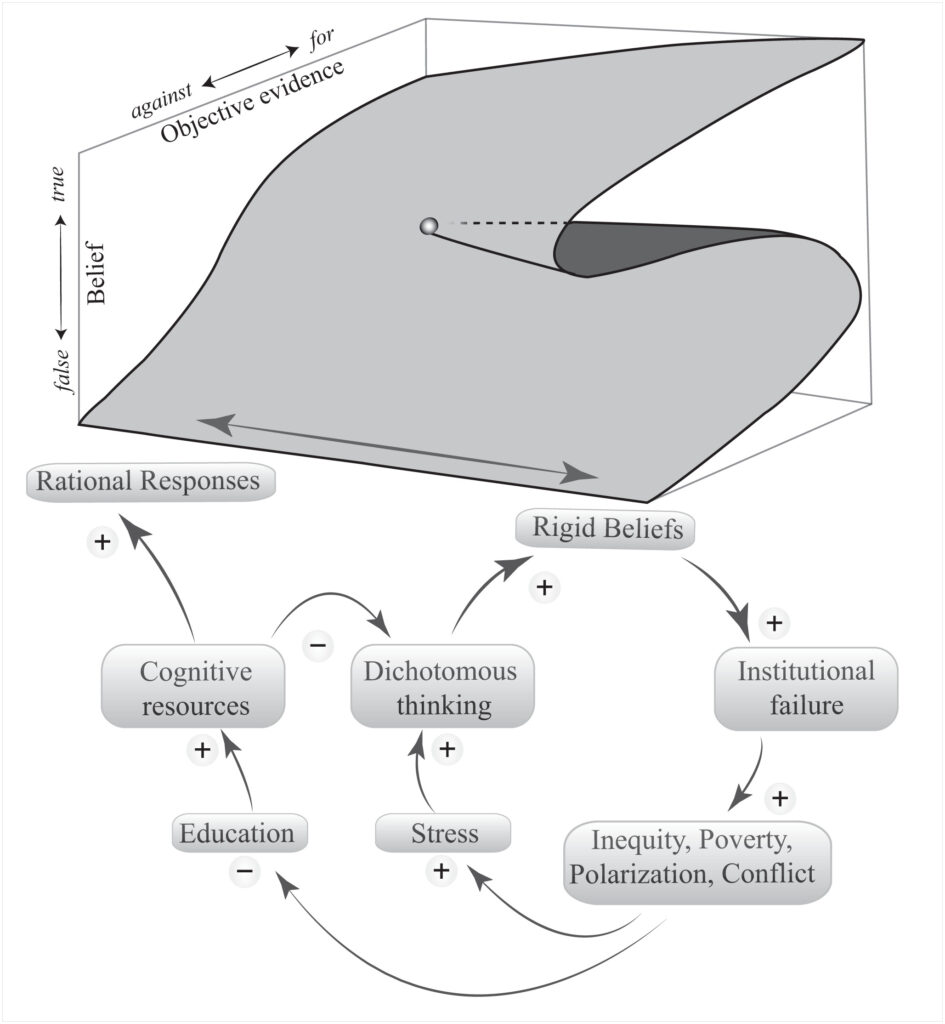

With organizations of all sorts facing increased urgency and unpredictability, being able to ask smart questions has become key. “The Art of Asking Smarter Questions” offers a practical framework for the five types of questions to ask during strategic decision-making: investigative, speculative, productive, interpretive, and subjective:

- Investigative: What’s Known?

- Speculative: What If?

- Productive: Now What?

- Interpretive: So, What…?

- Subjective: What’s Unsaid?

Leaders must invite dissenting views and encourage doubters to share their concerns. Cynefin offers for this an Aporia, a question is that you don’t know the answer—you have to think differently to resolve it

The post contains picture generated by Kandinsky bot by Sber AI